Probiotics & Prebiotics in Gut Health

Oct 2021

What are probiotics?

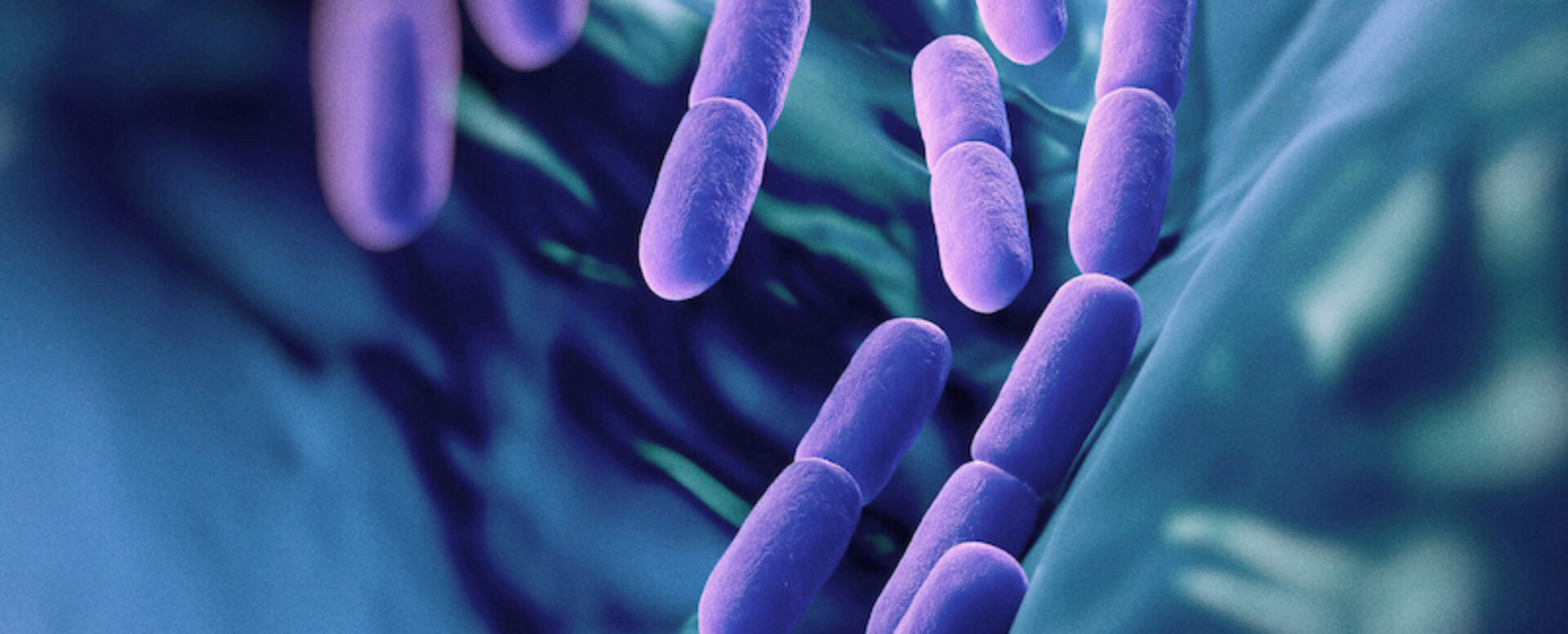

Probiotics are “live micro-organisms, which when consumed in adequate amounts, confer a health effect on the host”. Use of probiotic foods is an ancient tradition – even as far back as the time of Genghis Khan, fermented milk was being drunk as an elixir of strength and health.

In the second part of this gut health series, we are going to look at the role of probiotics and prebiotics in gut health – possibly one of the most exciting new topics to emerge in nutrition in the last few years. If you missed Part 1: The basics of gut health take a look at it first to give you a little more background.

Most often, probiotic foods or supplements contain strains of either Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium bacteria, usually from fermented dairy products. However, before starting to act, they have to survive the hazardous journey to reach our gut:

They need to first get through manufacturing, transportation and storage processes, to reach our fridge or kitchen cupboards alive and in good condition.

Then they must make it through the acidic environment of our stomach (designed precisely to kill off any wayward bacteria) and through the swamp of potent digestive juices and enzymes secreted by the gallbladder and pancreas.

Finally, if they succeed in reaching their destination, the large bowel, they then actually need do some good for the host rather than just going along for a free ride, or even possibly doing some untoward harm.

—

Because of these difficulties with getting the right probiotics to the right place, it is important to point out that the benefits which are seen in clinical trials may not all be possible to achieve with the yoghurts, tablets or other supplements available over-the-counter.Despite all these challenges, however, good quality strains of probiotics have been associated with beneficial effects in some disease processes, such as reducing antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Researchers are also examining a huge range of other conditions that may benefit from probiotics (Tuohy et al., 2003) (NHS Choices, 2015). Further research is very much ongoing.

Limitations: Most of the clinical research that has been carried out on prebiotics has been in unwell populations, and even then they are not yet in widespread use. We do not yet know much about the impact that taking probiotics might have in generally healthy people (Puupponen-Pimia et al., 2002). Anecdotally, I have found them to be of tremendous benefit for myself and some of my clients. However, anecdote is not a strong form of evidence, and I am always cautious about recommending any supplements on this sort of platform, so please do speak to your doctor or an appropriately qualified nutrition professional prior to commencing any supplements.

Furthermore, probiotics, even as tablets, are also still regarded as foods. Therefore they do not have to undergo the same rigorous testing as medicines do, so it is difficult to know if they actually contain the bacteria they claim, alive, in an adequate dose, and are able to give you a tangible benefit (NHS choices, 2015). The European Food Safety Authority has even gone so far as to ban the probiotic food industry from certain advertising claims, such as that they ‘boost the immune system’, because there is insufficient evidence to back such claims up at the moment. A healthy dose of skepticism is often helpful in nutritional science!

As Dr Alessio Fasano so neatly puts it, we can compare our current knowledge of the microbiota to our knowledge of space. We know the universe exists (our microbiota), and we are getting to grips with the fact the Milky Way is there (the major strains of bacteria), but we are far off knowing where London is! In other words, there is a lot of detail still to understand before we are able to fully utilize probiotics for health.

What about prebiotics – are they the same thing?

No. Prebiotics are a class of nutrients called ‘oligosaccharides’ (a type of fibre) which pass through the upper portion of the gut undigested, to feed and stimulate the growth of microbes further down. I think about it as nectar for gut bugs!

Types of prebiotic that are thought to influence the microbiota include (Tuohy et al., 2003);)

Inulin & Fructooligosaccharides – found in foods such as Jerusalem artichoke, asparagus, leeks, green bananas, chicory and onions (Sabater-Molina et al., 2009)

Lactulose

Galactooligosaccharides – found naturally in breast milk to help feed the microbiota of new born babies.

—

In general, a dose of more than 20g a day of all of these combined, may lead to unwanted side effects such as flatulence and bloating (Tuohy et al., 2003). I would therefore suggest it is a sensible idea to always ‘start low and go slow’ when introducing these to your diet.

As an added benefit, when our gut microbes break down these prebiotic fibres, especially inulin, they release a compound called butyric acid (Scott et al., 2013). This may be particularly important in gut health, as not only is it thought to be anti-inflammatory, but it also helps build up the gut defence barrier and decreases oxidative stress. Plus it might even help to signal to our brain that we are full and satisfied at the end of a meal (Hamer et al., 2007).

My pragmatic approach, if you are generally well, and would like to boost your probiotic and prebiotic intake, is to use foods first as much as possible.

In part 3 of this series,10 Ways to Help Support Gut Health, we will explore lots of practical ideas on how to do this.

You’ll find lots of recipes here rich with prebiotic foods – why not give some of these a try?

References & Bibliography:

Please note: This article is for information only and in no way replaces medical or personal nutrition advice. You should always speak to your healthcare provider in the first instance if you have any concerns whatsoever about your digestive or gut health. Please do not disregard or delay treatment based on anything you read on this website. I am not a doctor, nor am I your Nutritional Therapist. The information I share is very general and may not be relevant or appropriate for you as an individual.

Hamer, H.M., Jonkers, D., Venema, K., Vanhoutvin, S., Troost, F.J. and Brummer, R.. (2007) ‘Review article: The role of butyrate on colonic function’, Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 27(2), pp. 104–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03562.x.

NHS Choices (2015) Probiotics – NHS choices. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/probiotics/Pages/Introduction.aspx (Accessed: 11 December 2015).

Puupponen-Pimiä, R., Aura, A.., Oksman-Caldentey, K.., Myllärinen, P., Saarela, M., Mattila-Sandholm, T. and Poutanen, K. (2002) ‘Development of functional ingredients for gut health’, Trends in Food Science & Technology, 13(1), pp. 3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0924-2244(02)00020-1.

Sabater-Molina, M., Larqué, E., Torrella, F. and Zamora, S. (2009) ‘Dietary fructooligosaccharides and potential benefits on health’, Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry, 65(3), pp. 315–328. doi: 10.1007/bf03180584.

Scott, K.P., Martin, J.C., Duncan, S.H. and Flint, H.J. (2013) ‘Prebiotic stimulation of human colonic butyrate-producing bacteria and bifidobacteria, in vitro’, FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 87(1), pp. 30–40. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12186.

Tuohy, K.M., Probert, H.M., Smejkal, C.W. and Gibson, G.R. (2003) ‘Using probiotics and prebiotics to improve gut health’, Drug Discovery Today, 8(15), pp. 692–700. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02746-6.

Photos by Darryl Leja

MORE TO EXPLORE

Please note that the information on this website is provided for general information only, it should not be treated as a substitute for the medical advice of your own doctor or any other health care professional providing personalised nutrition or lifestyle advice. If you have any concerns about your general health, you should contact your local health care provider.

This website uses some carefully selected affiliate links. If you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission, at no additional cost to you. This helps to keep all of our online content free for everyone to access. Thank you.